Simon Drugda, PhD Candidate at the University of Copenhagen

The Rule of Law crisis in Europe is correlated to the contemporary rise of populism in the region. It is, therefore, crucial to observe the behaviour of populist actors in the position of power and critically examine their efforts to adopt changes to the government framework. Some such changes to the constitutional government may be aimed at the national level: to weaken representative institutions, rig elections, pack courts, or curb independent administrative agencies of the fourth branch. Other measures may be directed against the EU, which is often the target of populist rhetoric. More interestingly, proposals for constitutional change have utility even for populists out of power. Constitutional amendments generally attract attention, and can thus be used as a powerful tool to communicate a political message to a target audience. A comparative study of tricks in the populist playbook may allow us to identify emergent abusive strategies elsewhere before they are adopted domestically.

This contribution quantitatively examines the prolific drafting of constitutional amendment proposals by the far-right Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia. The current parliamentary term in Slovakia surpassed all previous terms on record in the number of submitted proposals for constitutional change, and almost a third of all proposals have been authored by the People’s Party.

Containing the Far-Right

The far-right party led by extremist Marián Kotleba entered the Slovak Parliament in 2016, carrying eight percent of the national vote. The outcome of the general election was interpreted to indicate worrying attitudes of the ethnic majority against the Roma, and “growing political hostility toward potential migrants and refugees who could augment Slovakia’s tiny Muslim population.”[1] Although the government has been purportedly trying to stop the rise of extremism since the election, intolerance and conflict remain prominent in the society as new clones of Kotleba’s party emerge.[2]

Benefits of Having a Seat in the Parliament

The presence of Kotleba’s party in the Parliament was a test to the Slovak liberal democracy. The question was how to contain the extreme right? Populists, even politicians with authoritarian tendencies have always been present in Slovak politics. However, this was the first time that a party, which had been previously disbanded for wanting to get rid of democracy got elected.[3] Having a party in the Parliament brings at least three benefits: a) MPs generally enjoy robust protection of speech;[4] b) parties with a yield above the five percent electoral threshold receive a financial subsidy proportionate to their share of the national vote; and c) parliamentary parties may partake in legislation and constitution-making. All these benefits will enable populists in different ways. This contribution only examines the last subject, looking at how Kotleba successfully exploited the low cost of initiating constitutional change in Slovakia.

Unintended Consequences of Non-Cooperation

Kotleba promised a lot during the campaign, but upon entering the Parliament, it became clear that almost no one wanted to cooperate with the far-right party. The government coalition took it upon itself to stymie the rise of extremist sentiments in the society; a claim that would not be credible if it was seen to be working with Kotleba.[5] Most of the opposition also rejected Kotleba, which significantly decreased chances for the People’s Party to implement its policy preferences and campaign promises, especially the promise to break up the establishment. A constitutional change in Slovakia requires a higher threshold for passage by the Parliament, which in turn may require some compromise. When all other parliamentary groups principally opposed Kotleba, however, he forswore negotiations. Since no other parliamentary group would support Kotleba’s agenda, there were no incentives for the far-right party to comprise or moderate its content. Instead, Kotleba focused on signalling to his electorate by invoking the most salient power of the Parliament: the power to initiate constitutional change.

Low Cost of Initiating a Constitutional Change

Over the duration of the parliamentary term, Kotleba’s party exploited rules on constitution-making to initiate disruptive proposals and blame failure on the “establishment.” The party effectively used constitution-making as a PR tool to attract media coverage.[6] Proposals for constitutional change have been until recently rare in Slovakia, at least when compared to a thousand legislative proposals tabled with the Parliament per term.[7] Constitutional amendments are visible because they require a higher threshold for adoption. Formal amendment rules in Slovakia prescribe an absolute three-fifths majority (90 out of 150 MPs) for a constitutional change. However, the costs of submitting constitutional proposals are much lower. MPs may initiate constitutional change relatively easily. The only constraints on the legislative initiative, including a draft constitutional amendment, are set by Standing Orders of the Parliament. The rules prescribe that proposals on the same subject cannot be re-introduced within six months after being voted down and debate on constitutional amendments must last at least 12 hours.[8] The higher threshold gives weight to proposals for constitutional change and makes them clearly distinguishable from legislation and ordinary business of the Parliament. Kotleba capitalised on the visibility of constitutional amendment proposals to attract attention.

Increasing Number of Constitutional Amendment Proposals

Since taking up their seats, the 14 MPs of Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia initiated more than 60 legislative proposals, among them a new law on the establishment of domestic militia and a law to restrict access to legal abortion. The far-right party also introduced 19 proposals to amend the Constitution; more than any other group in the Parliament. Some of the constitutional amendments were duplicitous, re-submitted two to three times after the lapse of the six-month preclusive period. None were successful. The average vote for all 17 proposals was approximately 19 MPs pro amendment. The highest vote was 24 and the lowest 14. Most MPs from other parties either abstained from voting on constitutional amendments proposed by Kotleba’s party or voted against them, which fitted the narrative that Kotleba wanted to portray.

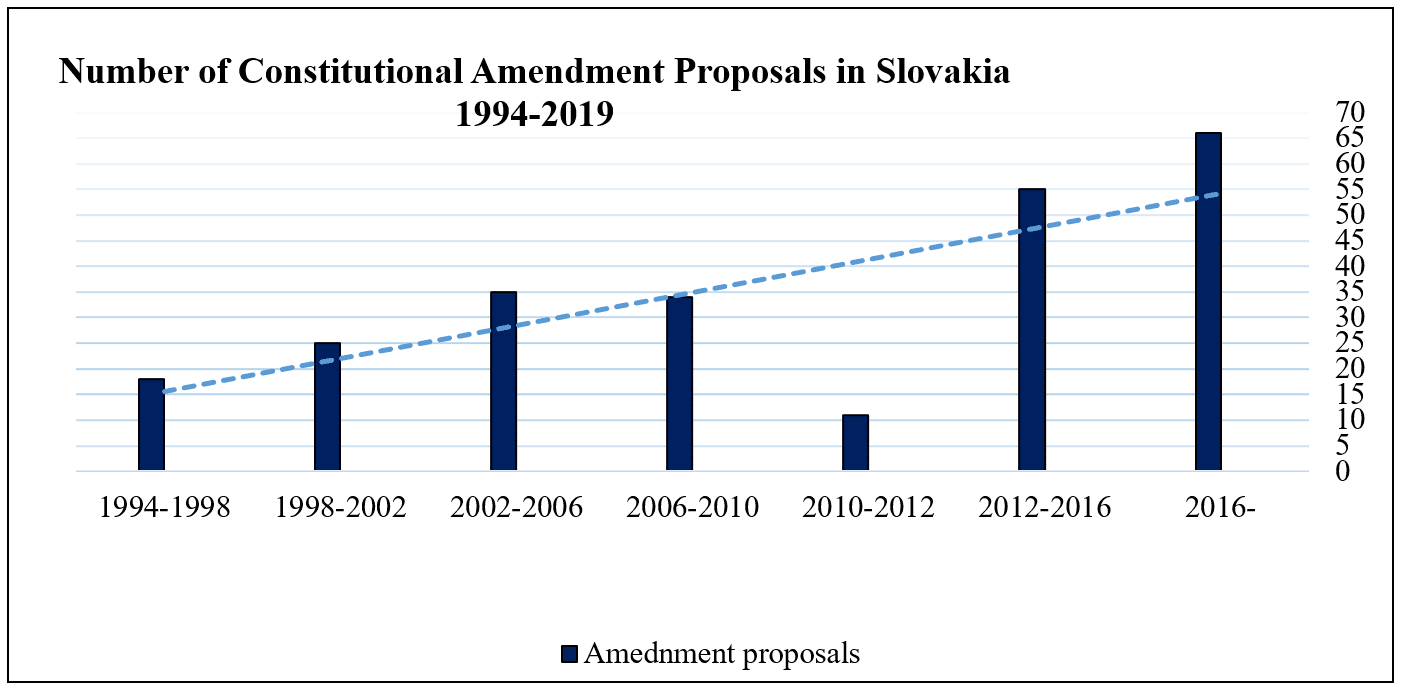

The prolific drafting of Kotleba’s party contributed to making the 7th term of the Parliament the one with most constitutional amendment proposals in history. MPs have proposed 66 constitutional amendments in the current term, and the number will likely increase since there is still more than three months until the next general election. Figure 1 shows the rate of proposals for constitutional change in the period 1994-2019. There is a clear tendency of MPs to propose more constitutional amendments each parliamentary term since the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic, which may potentially lead to instability and inflation of the normative power of the Constitution.

Conclusion

Kotleba’s MPs introduced almost a third of all proposals to change the Constitution in the 7th parliamentary term. There is not enough space to qualitatively review the proposals in this blog contribution, but they can be roughly classified into three categories: 1) changes that seek to enhance direct democracy at the expense of representative institutions; 2) proposals directed against the EU; and 3) proposals on budgetary responsibility, spending, and material resources. Instead of a conclusion, let us at least briefly examine the most prominent proposals in each category. Out of the three, constitutional amendments that fall in the first category seem more likely to have impact on the Rule of Law.

- Two proposals that may serve as good examples to illustrate the first category are constitutional amendments to reduce the size of the Parliament from 150 to 100 MPs and lower the quorum of a referendum.[9] The amendment to reduce the size of the Parliament has been already initiated three times by Kotleba’s MPs. They calculated that the cost of 50MPs is approximately 18 mil EUR per term, and argue that the reduction in size will unburden the state budget. A similar measure was recently passed by lawmakers in Italy, on the initiative of the populist Five Star Movement.[10]

- Efforts to deny the primacy of EU law in Slovakia may serve as an example of a constitutional amendment from the second category. This amendment has been likewise already introduced three times. The amendment would delete the second sentence of Article 7.2 from the Constitution, which reads: “The legally binding acts of the European Communities and the European Union shall prevail over the laws of the Slovak Republic.” Kotleba argues that the entrenchment of the principle of the primacy of the EU law meant the complete loss of sovereignty of the Slovak Republic.[11]

- Finally, Kotleba also repeatedly tried to entrench the protection of wood as a “strategic resource of national importance” to add it to the protection of water (Art 4.2) and land in (Art 44.5) that are both already in the Constitution. Such proposals are popular, although they rarely lead to effective protection of natural resources on the ground.

____________________________________

[1] Freedom in the World – Slovakia, Freedom House (2017)

[2] Intolerant attitudes have most recently found a proponent in the controversial Supreme Court judge Štefan Harabin, who founded a party called Homeland to run in the 2020 parliamentary election. When Harabin ran for President in September 2019, he spread disinformation about migrants and The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence.

[3] Kotleba’s previous party Slovak Togetherness was dissolved in 2006 by the Supreme Court because of advocacy for the division of society into estates, in which only select few would have the right to vote. “Extremist party outlawed” (The Slovak Spectator, 6 March 2006)

[4] One of the far-right party MPs, Milan Mazurek, insulted Islam as a “satanic and paedophile work of the devil” in the parliamentary Chamber and received a fine. Mazurek later lost his mandate after a Supreme Court decision for comments against Roma made outside of the Parliament. See “ĽSNS MPs got highest fine for statements on Islam” (The Slovak Spectator, 9 February 2019) and “Far-right MP Mazurek found guilty. He will lose his seat” (The Slovak Spectator, 3 September 2019)

[6] Kotleba’s party also poached the agenda of social-conservatives to acquire legitimacy with the mainstream voter.

[7] The Parliament reported 1149 legislative proposals by June 2019

[8] Legislative proposals also need to have accompanying documentation, such as the explanatory memorandum.

[9] Kotleba also proposed that the General Prosecutor should not be appointed by the Parliament but instead appointed by the judiciary, prosecution and members of legal professions. This constitutional amendment also proposed to introduce a popular recall of the General Prosecutor through a referendum.

[10] “Italy reduces size of parliament ‘to save €1bn in a decade’” (BBC News, 8 October 2019)

[11] The People’s Party currently has two MEPs, after the 2019 election. See the European Election Results by National Party: 2019-2024, Slovakia

The views expressed in this article reflect only the position of the author and not necessarily the one of the BRIDGE Network Blog.

Simon Drugda, PhD Candidate at the University of Copenhagen

Featured image credit: “slovak parliament” by Johannes Zielcke, CC licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0