Orsolya Farkas (Free University of Bolzano/Bozen)

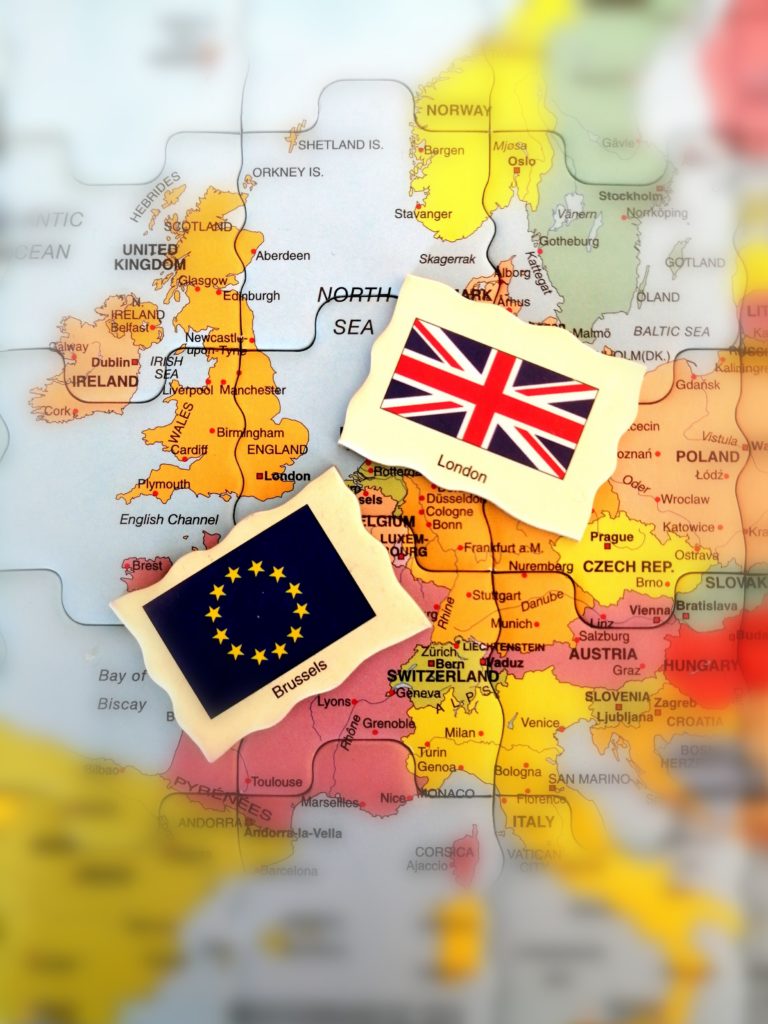

It has been clear since the very beginning that Brexit would fundamentally change the legal status of the approx. 1.2 million UK citizens living in Europe, and that those who are planning to move will find themselves in a new situation. But it was less expected that uncertainty – and, finally, 11th hour solutions – would be the characteristic features of the very last days of the Brexit process.

Throughout the Brexit process the loss of EU citizenship gained a symbolic value as this meant the loss of one of the most tangible results of the integration process in the social-political sphere. Many initiatives suggested various solutions to preserve at least partly the rights attached to EU citizenship for UK citizens: they run from political initiatives to legal challenges, including the proposal to create a European Green card or an associate citizenship status. Albeit all these attempts enjoy considerable moral support, their legal justification faces reasonable obstacles.

During the Withdrawal negotiations the Commission remained committed to protecting those people who saw their rights canceled while they were exercising them and who, with the end of the transition period, suddenly found themselves in a different legal environment on 1 January 2021. While the Withdrawal Agreement safeguards the residence rights of those who exercised their free movement rights and continue to do so after the end of 2020, the practical implementation of these rights is surrounded by uncertainty. The Member States can choose between constitutive and declaratory residence systems, but whatever is the option, UK nationals must present documentation and do some paperwork in order to have their residence rights confirmed. Based on highly variable national rules and on a patchwork of relevant case law, success of the applications is not at all automatic. In addition, the current pandemic does not ease the situation. As a recent study of the Migration Policy Institute shows, the public health crisis will slow down the residence registration process due to difficulties in the collection of biometric data for residence cards, lack of support for hard-to-reach groups with limited digital access or literacy, or the restrictions on in-person appointments in public offices.

Turning towards those who plan to exercise free movement from January 2021, the landscape is completely different: UK citizens coming to Continental Europe are treated as Third Country Nationals (TCNs). They can stay without a visa for maximum 90 days in each 180 days, even though this creates potential troubles e.g. for second house owners who used to stay longer. But more importantly, national immigration rules apply if one wants to work in Europe. A comparison among those who enjoy residence rights ensured by the Citizens’ Rights Directive (Dir.2004/38) and TCNs including long-term residents (Dir.2003/109) clearly indicates the limitations not only in terms of conditions, but also as far as the preservation of their status is concerned.

The Trade Deal achieved at Christmas opens up some space for closer relations between the UK and the EU in terms of free movement. With much uncertainty about the precise content and the way of practical application, the Deal contains provisions concerning the exemption of short term business visitors from visa obligations, the coordination of social security systems and the possibility of access to medical treatment. It remains to be seen whether these goals will remain wishful thinking or if they will ease in a meaningful way some aspects of free movement in the future.

Orsolya Farkas is lecturer at the Free University of Bolzano/Bozen