Ian Cooper (DCU Brexit Institute)

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has highlighted an important development in the politics of the European Union (EU) – the increased activity of regional groups of member states. The invasion provoked strong condemnation not only from the European Union (EU) as a whole (as seen last week’s European Council meeting) but also from regional groups of frontline states. The invasion was condemned by the Baltic Assembly, whose three countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) also worked together to expel Russia from the Council of Europe. The leaders of the four-nation Visegrád Group (Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) met with UK prime minister Boris Johnson to jointly condemn Russia’s actions (although there are recent signs of disunity within the group). A larger group of front-line NATO states, the Bucharest Nine (comprised of all the Baltic and Visegrád states plus Romania and Bulgaria) held an emergency summit in Poland the day after the invasion began, attended by Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen; this same group had also recently met in conference calls with the US President, Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. Other groups of states that came to the fore as the crisis developed include the Weimar Triangle (France, Germany and Poland) and the Slavkov Triangle (Austria, Czechia and Slovakia). Even close watchers of EU politics might have some trouble keeping track of all these regional groups.

Some basic facts about these regional groups are elusive. How many are there? What do they have in common, and how do they vary? What purposes to they serve? What effect do they have on European integration? These questions are addressed in a new paper co-authored by myself and Federico Fabbrini, which sets out to describe and explain these phenomena, which we refer to as BURGs (Bottom-Up Regional Groups). They are forms of “bottom-up” cooperation that are institutionally separate from the EU, residing at a middle level between the national and EU levels of authority. As such, we argue that they are a form of differentiated governance in the EU that has hitherto gone largely unexplored.

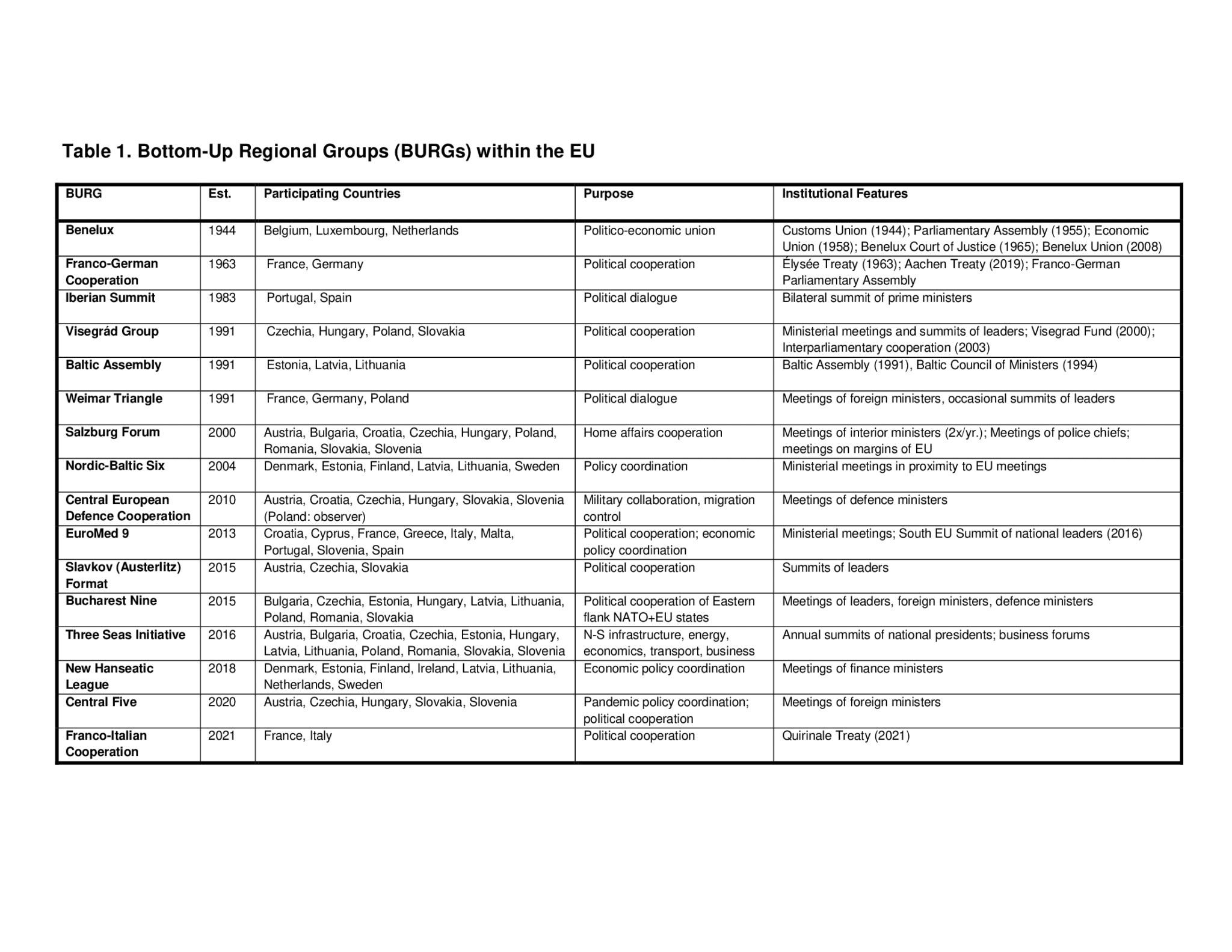

We define a BURG as a form of international cooperation that meets the following five criteria: (1) it is institutionalized cooperation; (2) it is currently active; (3) its participants are all current EU member states; (4) it is institutionally separate from the EU; and (5) the participating states are geographically proximate, by belonging to the same regional area of the EU. Applying these criteria, one can identify 16 BURGs within the current EU-27 (see Table 1). These vary in size from a minimum of two (e.g. Iberian Summit) to a maximum of twelve (Three Seas Initiative). Perhaps surprisingly, many of these are relatively new: while the oldest BURG, Benelux, dates back to 1944, more than one third (6/16) have been created since 2015, and the newest is merely four months old (Franco-Italian cooperation, based on the Quirinale Treaty of November 2021).

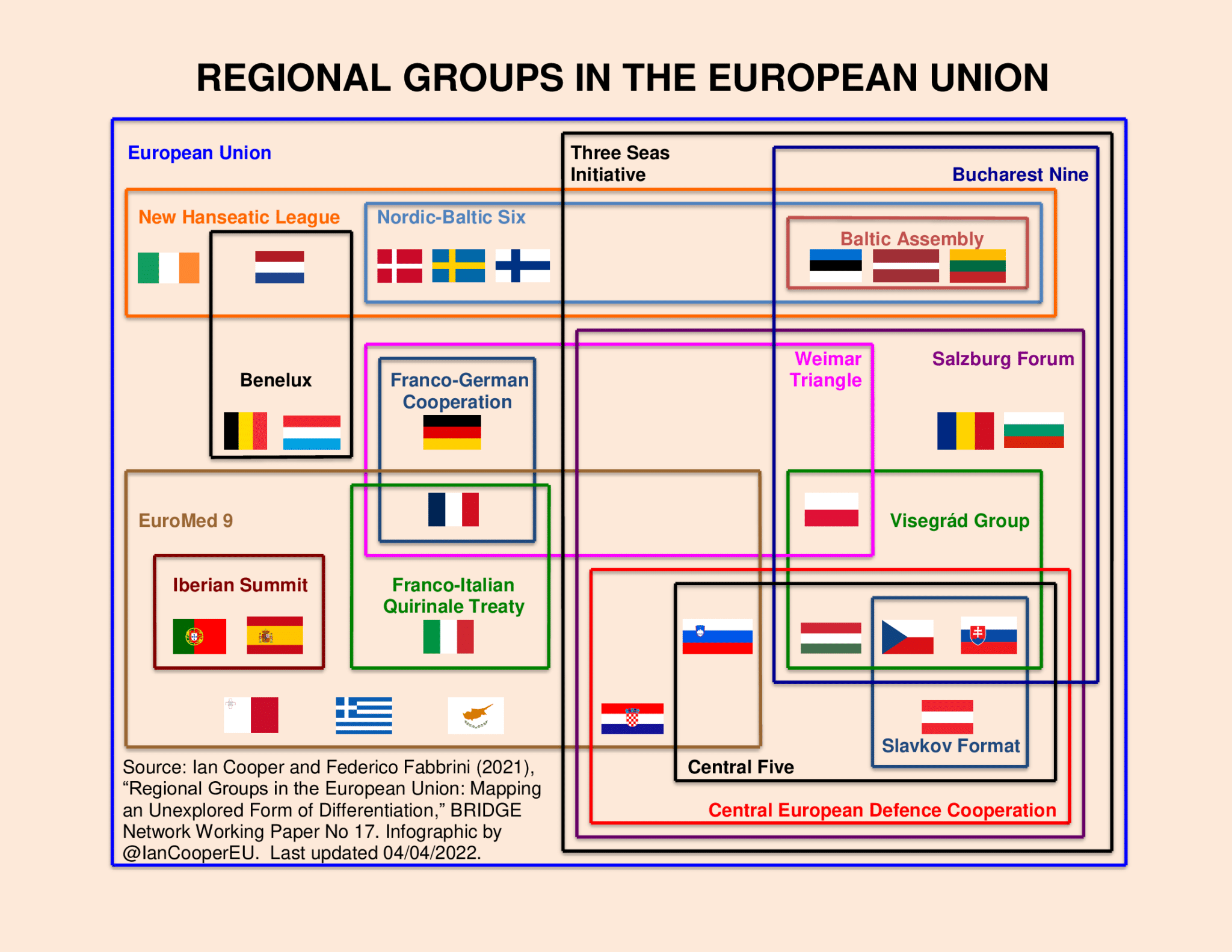

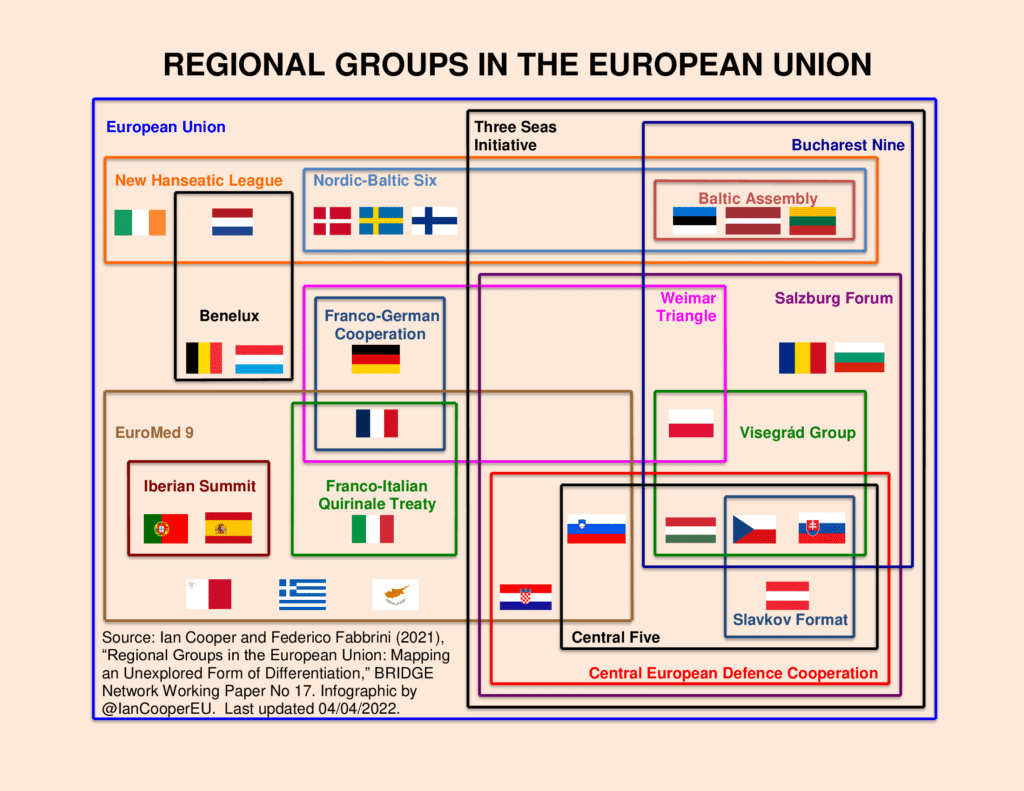

The various inter-relationships between the BURGs are displayed in this Diagram. Each EU-27 member state participates in at least one BURG, but most participate in more, up to a maximum of six (which is the number for Czechia and Slovakia). BURGs are found in every region of the EU, broadly understood – North, South, East and West. However, the density of BURGs is actually greater on the right side of the diagram occupied by the states of Central and Eastern Europe that joined post-2004 (along with Austria). Some of the BURGs are “nested” inside one another (e.g. from smallest to largest, Slavkov Triangle, Central European Defence Cooperation, Salzburg Forum, Three Seas Initiative), whereas others are adjacent (Baltic Assembly, Visegrád Group) or, more frequently, overlapping (e.g. Weimar Triangle, EuroMed 9). The information in this diagram has never before been gathered in a single place.

Our analysis also shows that while they share these basic commonalities, BURGs also differ from one another in four imporant ways – their longevity (pre- vs. post-accession), level of institutionalization, policy scope, and degree of activity. In terms of longevity, BURGs may be created by non-EU member states that subsequently join – indeed, in many cases they are organized to aid the accession process – or by existing EU member states, or a mix of the two. BURGs vary widely between those that are highly institutionalized (e.g. Benelux, a complex organization with its own intergovernmental council, committee of ministers, parliamentary assembly, court of justice and secretariat) and those that are miminally instututionalized (e.g. Nordic-Baltic 6, described as “merely a loose, informal club whose members have a habit of consulting and coordinating with each other”). Furthermore they vary between BURGs which may look at a wide array of policies (e.g. the EuroMed 9) or those which focus on one sectoral policy (e.g. the Salzburg Forum, focused on Home Affairs). Finally, they differ in their level of activity: some meet regularly and frequently, whereas others more sporadically or on an ad hoc basis.

What purpose do the BURGs serve? We identify a rough typology of four ideal-types of BURGs – what we call integration vanguard, functional cooperator, policy coordinator, and resistance cell. The list is non-exclusive, meaning that a BURG might fulfill multiple purposes at once, and the purposes it serves might change over time. These kinds of BURGs emerged – broadly in this order – through the history of the European integration process. An integration vanguard is a group of states that pursues further integration among themselves with a view to promoting integration in the whole of the EU. The best examples of this are Benelux and Franco-German cooperation, although in different ways: Benelux, begun in 1944 before postwar European integration started, is a model, in that it established forms of institutional cooperation among the three countries, e.g. the customs union, that would later be adopted by the EU as a whole. Franco-German cooperation is a motor, in that the two countries jointly initiate further integration with a view that it should be adopted by the EU as a whole. A second purpose of a BURG may be as a functional cooperator, focused on internal cooperation among the participating member states, often in a particular sectoral or functional area (e.g. Salzburg Forum, Central European Defence Cooperation). The third purpose of a BURG is as a policy coordinator that is focused externally on the EU level, in which participating states coordinate their policy positions within EU forums such as the Council and European Council. Examples of BURGs whose purpose is policy coordination is the Nordic-Baltic Six, the EuroMed 9 (made up since 2021 of the nine Mediterranean EU member states – Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain) and the New Hanseatic League (made up of the NB6 countries plus Ireland and the Netherlands). Fourth and finally, there is the possibility that a BURG could act as a resistance cell, a group of member states would actively work together against the fundamental values of the EU. The most prominent example of a BURG taking action of this kind – although one that is highly contested – is when the Visegrád Group acted to thwart the implementation of the proposed relocation mechanism of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) in the wake of the migration crisis of 2015-2016. (However, it should be noted that these countries have taken a very different approach in recent weeks, welcoming refugees from the war in Ukraine.) This typology of the purpose of BURGs shows that their effect on European integration may be positive, negative or neutral.

Our article concludes that BURGs are a form of differentiated governance in the EU, albeit one that is not always recognized as such. This is because much of the analysis of differentiated integration is focused on the extent to which common EU rules are not applied uniformly across the EU due to the various derogations and opt-outs that apply to different member states. In their book Ever Looser Union? (Oxford University Press, 2020) Schimmelfennig and Winzen narrowly define differentiation as a situation arising “when the legally valid rules of the EU, codified in EU treaties and EU legislation, exempt or exclude individual member states explicitly from specific rights or obligations of membership”; by their own admission, this leaves out the phenomenon that arises when “groups of members [states…] cooperate informally besides and beyond the institutional formats and legal rules of the EU” (p.3-4). Our article seeks to remedy this gap in the literature by giving a comprehensive survey of the intra-EU BURGs. They are a phenenomenon of rising importance, as evidenced by their increasingly prominent role in the EU’s response to the crisis and war in Ukraine.

More Information can be found on these and other groupings by taking a look at our Interactive Maps.

Ian Cooper is a Research Fellow at the Brexit Institute at DCU. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Yale University. He has previously held academic positions in the UK, Norway, and Canada and most recently he was a Jean Monnet Fellow at European University Institute in Florence, Italy.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the BRIDGE Network Blog.