Orsolya Farkas (Free University of Bozen-Bolzano)

The border emergency attracts much media attention, public upheaval and plenty of emotions, but a more generalized attitude towards immigration is strongly influenced by the success of integration policies. In thinking about the fate of those who reach European shores, the wider public does not necessarily differentiate between asylum seekers and economic migrants. If the generalized experience of the integration of immigrants is positive, then the public attitude is more accommodating towards new arrivals, whereas in the opposite case less tolerance is shown and even hostility can arise.

Among the various components of immigration policies, education certainly plays a crucial role. On the one hand, for young immigrants schools are seen as the main place of interaction and socialization with the host society. On the other, education and training are determinant for their personal future just as for their ability to contribute to economic prosperity.

The aim of this blog is to briefly explore the specific situation in Italy and to examine its education policies towards students with migrant backgrounds. To avoid the risk of using too critical a lens in penning the picture, Italian integration policies should be placed in a wider comparative context. According to the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX 2020) Italy has performed fairly well, scoring slightly above the average of 56 countries. Its integration policies have been judged overall as “slightly favourable”, though in the field of education the outcome was “halfway favourable”. This indicator comprises factors such as access to education, targeting policies to specific needs and intercultural aspects of national education policies. Although most countries are slow to respond to changes occurring in their societies and to accommodate the needs of vulnerable children, this does not prevent our shedding light on some critical aspects and to indicate tools for improvement.

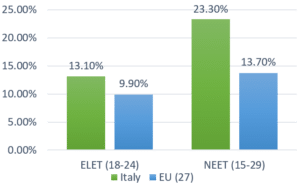

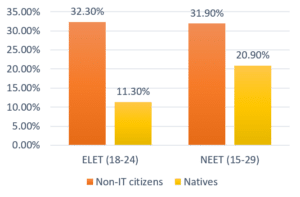

Also there are other indicators which underpin a critical view on educational achievement in Italian schools: taking into account all young people in the relative age brackets, the percentage of those (18-24) dropping out or leaving early from education and training (ELET) amounts to 13.10% against an average of 9.90% in the EU(27). As far as young adults (15-19) who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) are concerned, their share amounts to 23.30% in Italy compared to 13.70% in the EU(27). If this already alarm raising data is broken down between Italian and non-Italian citizens, one can see that in relation to early school leavers (ELET), 32.30% of students with non-Italian citizenship are concerned, compared to 11.30% of native students. Similarly, though to a smaller degree, a higher share of non-Italian young people are among NEETs than natives: 31.90% against 20.90%

[1] Save the Children, Atlante dell’infanzia a rischio, 2021, Il futuro è già qui, pp.166-167

[2] Fondazione ISMU, 26° rapporto sulle migrazioni, 2020, p.128

[2] Fondazione ISMU, 26° rapporto sulle migrazioni, 2020, p.128

Again, this problem is not confined to Italy, and the Commission’s Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021-2027, confirms the urgency of interventions devoting particular attention to schools and education. The Action Plan identifies major risk areas for people with migrant backgrounds compared to natives, such as dropping out from education, low level of educational attainment, low level of employment rate, exposure to poverty and social exclusion. To decrease these risks and to construct European societies which are more cohesive, resilient and prosperous, will require integration and inclusion. This process starts at schools, where education is seen as the foundation of successful participation in society; schools have the potential to be real hubs of integration for children and for their families. To this end, schools and teachers must be equipped with the necessary resources and skills; they must be prepared to support students with migrant background throughout their education.

Therefore, the question arises, how will such goals be achieved in Italy? What is the legal environment in which the Action Plan is implemented? Which aspects can be identified where legal tools can induce positive changes?

Looking at the Italian legislation in a historical perspective, a gradual opening towards vulnerable students can be observed since the beginning of the 1970s. In a nutshell, the process started with the end of school segregation for students with disabilities, later the protection of was extended to students with special learning difficulties and in 2012-13 measures were introduced for students with cultural, linguistic and social-economic disadvantages, including students with migrant background as well. For today, the Italian legal framework can be described as one which accommodates various types of vulnerabilities, but the norms protecting the right to education of students with disabilities are more articulated and more guarantees are available for this category than for students with migrant background.

For a better understanding, it is important to clarify that today the underlying concept in education is inclusion, which prevails over integration. The two concepts can be contrasted through the definitions elaborated by the UN Committee which supervises the implementation of the Convention of the Rights of People with Disabilities. It spells out that integration is “a process of placing persons with disabilities in existing mainstream educational institutions, as long as the former can adjust to the standardized requirements of such institutions.” Whereas inclusion is defined as follows: “it involves a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences”. The concepts were defined in relation to the right of education of students with disabilities, but today inclusion is applied in relation to all students.

However, (most) students with migrant backgrounds are subject of immigration rules as well and these rules placing special emphasis on integration. According to these rules, schools constitute a privileged space in the process of integration through teaching Italian language and civic education. But reality is more complex, and schools themselves cannot be insensitive to challenges: today approximately 10% of students have migrant backgrounds, including first- and second-generation migrants, refugees, unaccompanied minors, EU and third country citizens; they all face very different problems and they have different needs in education.

Therefore, a model of integration in an inclusive school seems to be appropriate as it captures both applicable concepts: integration refers to the necessity to acquire linguistic and other knowledge to adjust to the requirements of schools, whereas inclusion encapsulates the creation of a learning environment where all students can develop their full potential. Such a model is envisaged in the Ministerial Guidelines for the Welcome and Integration of Foreign Pupils.

Turning into the implementation of these concepts, various critical aspects can be detected. Perhaps the most relevant one is that the difficulties of students with migrant backgrounds are considered as temporary ones and principally linked to language. It is often thought that young people quickly absorb the new language and adapt to the new environment. Indeed, many measures and tools available at schools follow this idea. However, such a reasoning can easily lead to partial and misleading conclusions, as students with migrant backgrounds often have to face more complex and long-lasting problems. These can derive e.g. from traumatic experiences during the migration process or from their families’ social-economic situation. Various bottlenecks can be identified, where existing measures cannot, or do not ensure the desired outcome: support for learning Italian is available, but only for a limited period of time and not until proficiency is reached; students in need can receive support from their teachers, but this does not mean individual guidance and tutoring to efficiently contrast social disadvantage and educational poverty. Last but not least, teachers enjoy a wide discretional power in using personalized study plans and other support measures. All these elements affect the effective exercise of the right to education and the current legal framework does not provide for adequate guarantees where all learners enjoy substantial equality.

Legislative changes in the indicated direction would contribute not only to a better integration and inclusion in general, but the outcome would be measurable in areas of major concern for students with migrant backgrounds, such as delay and holding back in school completion or early drop-out. Furthermore, many talented students with migrant backgrounds would be able to choose among different pathways in education with better chances towards tertiary education and to invert their current overrepresentation in vocational education. Ultimately the interventions would generate positive changes in the risk areas identified by the Commission’s Action Plan as well. But perhaps most importantly, education would fulfill one of its primary goals, that is to enhance social mobility, decouple educational attainment from social, economic or cultural status and break the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

The considerations presented here were inspired by a vision about schools, about their duty towards future generations. This vision was recently so neatly expressed by the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella in his message to the Parliament on the day of his swearing in: “We support a school that knows how to welcome and transmit competence and culture, as a set of values and principles that are the bedrock of the reasons for our being together; school aimed at ensuring equal conditions and opportunities.”

Dr. Orsolya Farkas is member of the BRIDGE network. She is also involved in an interdisciplinary research project called DISCO – Diversity and Inclusion in Schools: Legal Solutions and Good Practices at the Free University of Bozen/Bolzano.

The views expressed in this blog reflect the position of the author and not necessarily that of the BRIDGE Network Blog.