The Governments of France and Germany recently presented a joint document introducing their proposals for an EU-wide response to the pandemic. The package includes the development of an EU “Health Strategy”, a plan to speed up the green and digital transition, another plan to enhance the EU Single Market and, finally, the establishment of an ambitious “Recovery Fund” for solidarity and growth.

It is crucial to read the proposal within this broader context in order to understand its aim and scope. The background of the Covid-19 crisis, jointly with the empowerment of the Single Market together with the digital and green transition is clear evidence of the specificity of the Recovery Fund for the current emergency, thus downplaying the expectations of those picturing such a measure as the “political noyau-dur” of a future joint debt instrument. The first impression from the reading of the document is that it represents a proposal for the establishment of a grant-based fund to which the EU Member States can apply that should be incorporated within the Multiannual Financial Framework of the EU, and, accordingly, relying mainly on an augmentation of the EU budget.

The main difference, according to the proposal forwarded by the two EU Member States, lies in the fact that the EU Member States are to entrust the European Commission with the possibility to borrow credit on the markets in order to finance the effort to tackle Covid-19. There are both problems and opportunities with such an approach. I will try to outline those briefly, starting with the problematic points.

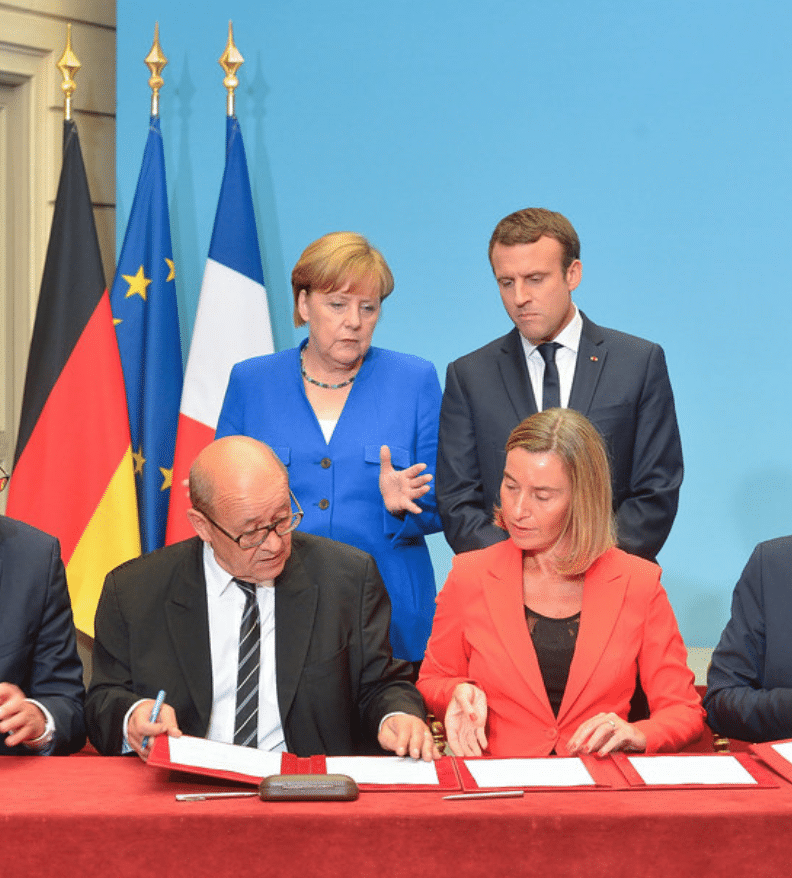

The Consolidation of a Franco-German Bloc at the Heart of the Union

This is a joint proposal by the two most influential EU Member States since the Meseberg Declaration. While it is, of course, possible for every Member State to propose their plan to the fellow Union Members, to understand if it is appropriate is another matter. The idea of bringing forward another rather radical proposal by France and Germany is problematic, as it gives the idea, to the other Member States but, most importantly, to other members of the international community, that there are prioritized fora for discussion within the EU. It is not a surprise that Member States with more parsimonious views regarding the EU budget and its spending capacity (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden – with the unfortunate nickname, the “Frugal Four”) have already started to draft a parallel proposal to downplay the “too generous” Recovery Fund. This might suggest, accordingly, that there is an ongoing feud at EU level between more powerful and influential States and smaller ones. The Franco-German block is nothing new, however, and, as the Schuman Declaration, whose anniversary was recently marked reminds us, the purpose of the EU was, since its inception, to bring together France and Germany. Proposal like this go a long way in demonstrating how successful the plan was: however, one should not forget that the other Member States, with different or competing views, might be inclined to oppose this alliance.

The Suitability of the Treaty Architecture for a Recovery Fund

The main concern with the implementation of instruments such as the Recovery Fund, which are introduced to share the risks associated with a common threat, is that the Treaty framework was not drafted for circumstances such as these. What needs to be assessed is whether there is a manifest prohibition under the Treaties for the adoption of such an instrument. The prohibition of overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility in Article 123 TFEU applies to the European Central Bank, whereas the Franco-German proposal refers to the European Commission borrowing money in the markets. This may be sufficient to prima facie avoid the prohibition established in Article 123 TFEU. On the contrary, it might not be sufficient to win the necessary majority for the adoption of EU law, especially if Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Netherlands are joined by other seemingly reluctant EU Member States, such as Hungary and Poland. It must be, however, noted that the latter two, despite several attempts to undermine rule of law, have always manifested a positive attitude towards initiatives aiming at granting additional economic resources to the Member States, and are thus unlikely to openly oppose similar proposals. In the event the Member States judge the Treaty framework to be insufficient, they will have to opt for an expedited EU Treaty amendment, which has only been used once: an amendment was introduced in 2012 to allow the incorporation of the ESM into the framework of the EU Treaties framework (which is still unused, as the ESM remains an intergovernmental instrument).

Paving the Way for a Common Debt Instrument?

With the caveat expressed above, the Franco-German proposal is surely interesting and can help the EU Member States to advance the fight against the pandemic and, more importantly, into the provision of a common solution to the current crisis. If this proposal is successfully adopted, it will – most likely – may represent for a stepping stone towards a future introduction of a common fiscal capacity and, more importantly, common debt instruments. From a legal standpoint, however, despite the fact that the Recovery Fund should be financed by the European Commission borrowing on behalf of the EU, it is still only a temporary grant-based mechanism that, despite its importance and size (500 B €), is very far from representing a real risk-sharing instrument. It remains to be seen whether this plan succeed despite the ongoing tension between the Member States and the EU level and the divisions between the Member States themselves. Only time will tell, but the previous experiences with the ESM and the Eurozone budget are surely not encouraging. The fact that, at the same time, one of the most important national constitutional courts (the Bundesverfassungsgericht) recently questioned the work of the ECB in answering the economic crisis, even amid the lockdown measures introduced by the Member States, illustrates the challenge for those who would advocate EU-wide, as opposed to purely national, solutions to common European problems.

Giovanni Zaccaroni is a postdoctoral researcher in EU law at the Brexit Institute and a member of the BRIDGE team

Image credit: from “Federica Mogherini in Paris for the launch of Alliance for the Sahel, July 2017” by European External Action Service – EEAS is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0